LULU 1978

From the Plays of FRANK WEDEKIND and the Opera by ALBAN BERG

THE BACKGROUND STORY

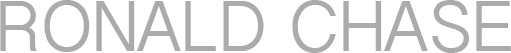

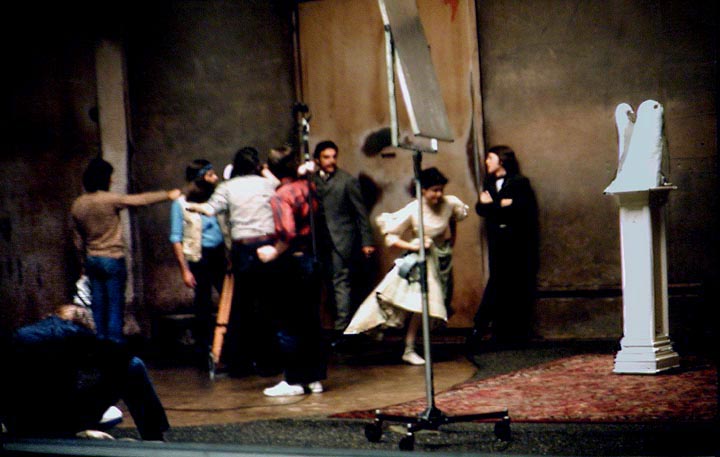

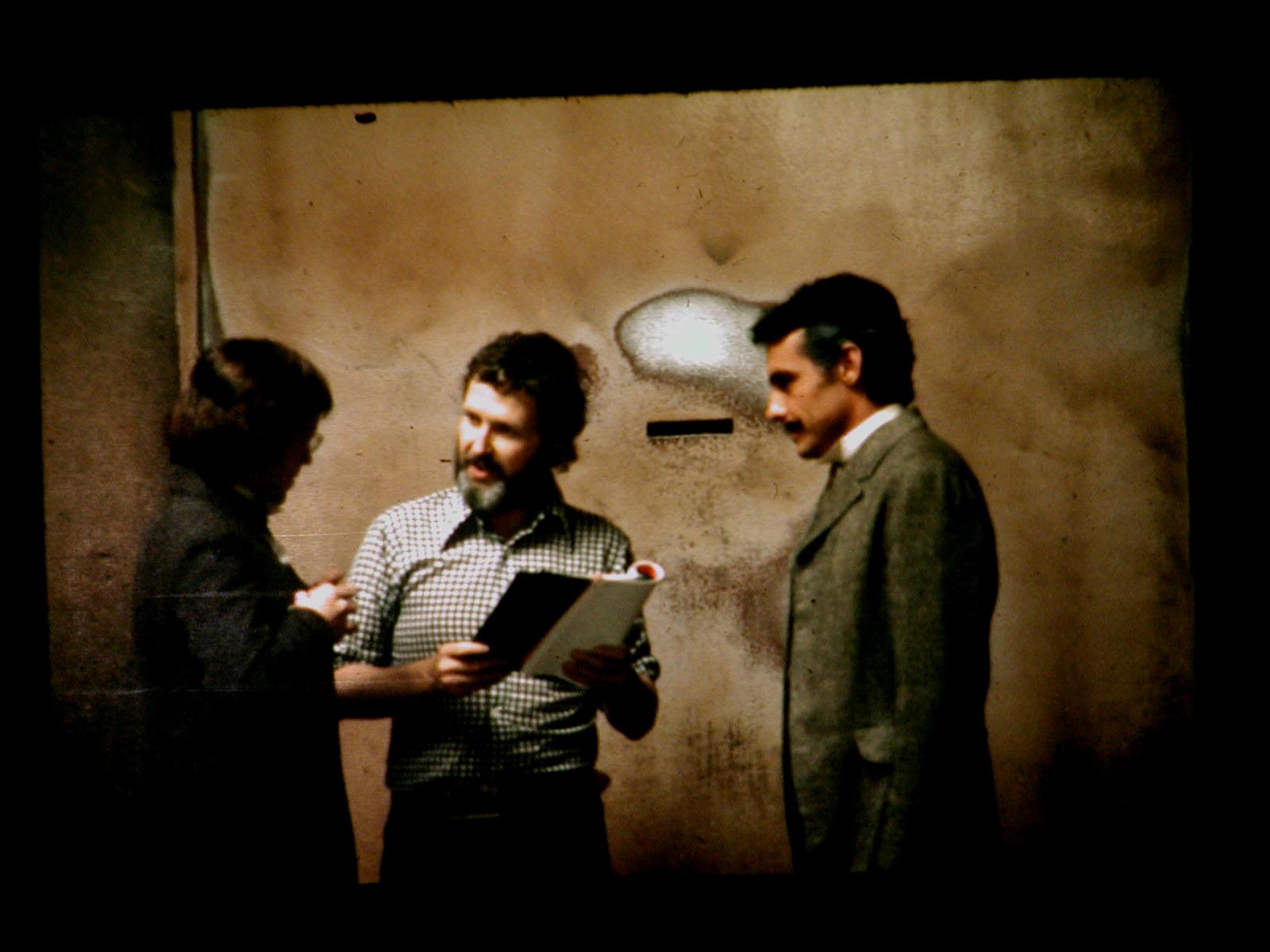

Lulu was filmed in San Francisco in the summer of 1974. Interiors were created in the warehouse at 136 the Embarcadero, and the auxilary scenes were filmed in the elephant cages of the San Francisco Zoo. These scenes were to be used for the Houston Opera’s production of Alban Berg’s opera, Lulu. Chase found additional funding, and asked many actor friends to volunteer in the cast. Paul Shenar was one of the leading actors at the American Conservatory Theater. Elisa Leonelli who had not acted in films before, was introduced to Chase by a close friend in Rome. The filming was completed at the end of August, and all the crew then set out for Europe, where another project was filmed for two weeks in Europe. (see Bruges-La-Morte). When Chase returned his editor informed him that there simply wasn't enough footage to make a feature film of Lulu. The scenes were edited for the Houston production (and played simultaneously with the staged action) but the film project was declared dead and void.

Production Stills at San Francisco Zoo.

One year later, Chase returned to the project and decided there really was enough footage to mold into a film. He re-thought the entire project. The film now was silent, with dialogue cards, and rearranged material--beginning scenes contained the most artifice and move toward a strict realism in the final scene. At one moment the film bursts into sound, utilizing the most effective dialoug scene from the original shoot. In March 1977 all the actors returned for a long weekend of filming the close-ups and moments missing from the first shoot. Piano music from the period, and appropriate small sections of the opera added to the atmosphere. An elaborate soundscape was created by a friend, Todd Boekelheide. (Academy Award for Amadeus) After its run at European festivals in 1978, the film was scheduled to open at La Pagode in Paris. However, the company who owned the rights to the Berg score refused to approve the music rights and the film had to be shelved. Chase felt the score was an essential part of the film, too important to be abandoned.

1978 FESTIVALS

Lulu was given its Europeon debut at the Rotterdam Film Festival in 1978. It was chosen by the Berlin Film Festival, London Film Festival, Dublin Film Festival, Deauville Festival, FILMEX, Los Angeles, Florence Film Festival of American Films, Ghent FIlm Festival, and Brussels Film Festival.

Selected as one of the 3 best films of 1978 by Paris Match.

INTRODUCTION TO THE FILM

Lulu is the fourth film version of the two plays by Frank Wedekind, Earth Spirit and Pandora's Box. The first was a silent film in 1923, the second and most famous, is the Pabst version in 1929 and there is also a version by the Polish director, Walerian Borowczyk for French television in 1980. Chase had admired the Pabst version, which he had seen in his college years, and it had led him to a deeper study of Wedekind. Chase directed a production of Wedekind's Spring's Awakening for his senior directorial thesis at Bard.

Through these earlier film versions, the popularity of actress Louise Brooks (the Pabst Lulu), and the rising prominence of Alban Berg's opera of the same name, Lulu has become an international icon for a femme-fatale. However, in Wedekind's work she is much more complicated . She remains almost guiltless and innocent --more of a symbolic receptacle in which men place their sexual desires, their fantasies and emotional baggage only to have them destroyed when facing reality. A huge part of the Wedekind is a condemnation of a repressed and hypocritical society, especially from a man's perspective. He was one of the first writers (an acquaintance of Freud) to put his finger on one of the sources of men's persecution of women --their fear of a women's " sexual power" that might their reason. She also is a symbol of what might be called joyous lust, natural instincty in man reviled by religious authority, and also condemed as a threat to “pubic morality”. Certainly this accounts for the wide range of interpretations given Wedekind's two plays. From a man's perspective it is obviously misogynistic, from a woman's perspective it is a harbinger of women's liberation.

In an interview at the BERLIN FILM FESTIVAL in 1978, Chase had this to say:

"I was attracted to its visionary attitudes, its modern ideas about women's liberation. If you look at the play superficially, you might think it was by a man who hated women. But I think as Wedekind went deeper into ideas he didn't quite understand, he came up with a portrait of a woman in a mythological sense, a very classic femme-fatale that defied cliche definitions. He understood something about the toxic attitudes of men toward women. He wanted to shock his audience into recognizing their duplicity in the hypocrisy of the era —and purposely created the Countess Geshwitz, the first lesbian in the history of theater to make his point about persecution.

He was interested in the psychological states of perversity, which makes the material extremely contemporary. Take the dialogue–– bits seem almost to be written yesterday: they're all about sexual roles, about changing identity, men becoming women, women becoming men; they have to do with a woman who is used by other people but somehow manages to understand them and get back at them while remaining completely innocent. She remains a force of nature."

GENE YOUNGBLOOD (author of Expanded Cinema) wrote this about the film:

It isn't a remake. Nor is it a cultish "homage" for the edification of film buffs. Rather it is an impressionistic meditation on, and evocation of Pandora's Box as a prophetic cultural myth, as collective erotic dream. All the characters are there, but they are given not as realistic characters so much as archetypes. Lulu still belongs to another era (title cards are used throughout) but, viewed from the perspective of the 70's , its psychological insights and social prophecies seem like revelations. Chase evokes rather than imitates the style of Pabst & Wedekind. On one hand there's Wedekind's synthesis of comedic, dramatic, farcical and satirical forms. On the other hand there's Pabst's dramatic framing and moody chiaroscuro. The movie starts at a feverish pace, moods and styles shift in rapid succession; gradually the film loses its artifice, scenes are longer, sync-sound dialog is heard. A foreboding realism encroaches as Lulu's thoughtless lifestyle propels her toward her tragic destiny. The last scene is silent, in darkness and overwhelmingly powerful. It should be noted that never has a "silent" film had such a rich aural texture. The sync and voice-over tracks are works of art in themselves, the non-programmatic use of Berg's opera is inspired, and a haunting piano score perfectly augments the film's obsessive nature.

LAWRENCE WESHCHLER http://lawrenceweschler.com/ An article for TAKE ONE 1978

In the great, late-Victorian, sex-vexed, expressionist tradition –the dark and riddled tradition of Strindberg, Ibsen, Munch and Freud—the German playwright Frank Wedekind commands a central and seminal position. Although not as well known today as some of his contemporaries, his influence permeates the world of his successors. The recent resurrection of two of his plays, Erdgeist and Pandora’s Box, by independent filmmaker Ronald Chase in his cinematic rendition of the Alban Berg opera which they inspired, Lulu is resolutely true to its sources—spellbinding, chaotic, provocative, disturbing, perplexing, and finally, infuriating.

For the past ten years Chase has been exploring the borderline between cinema and live theater, particularly opera, deploying floating screens and simultaneous projections in innovative stage productions throughout America. Following his 1975 collaboration with the Houston Opera Company on Berg’s Lulu, however, Chase took the process a step further, using material he had generated for the opera as a starting point for a full-length feature, one which returned to the original Wedekind sources. Chase’s Lulu has been creating a sensation at many international film festivals, notably the recent L.A. Filmex.

Wedekind’s two plays trace the story of Lulu, a provocative innocent whose vibrantly erotic life force, desperately miscast within the hysterical confines of Victorian society, inadvertently brings about the deaths of three successive husbands and is only stilled, at the play’s conclusion, by her own murder at the hands of Jack the Ripper.

Chase casts his Lulu in a plush, supple visual style, rich in shadows and purples, intoxicated with the textures of flesh and fabric. Much of his most beautiful footage was shot in the makeshift sets located in the elephant cages at the San Francisco zoo, and indeed the entire story seems to turn on the way an arbitrary captivity (the thick walls, the recurrent rumble of the sliding iron doors) slowly strangles the expression of natural instincts(the pure animal drive of the sexual so tellingly evoked through a leitmotif of bird and tiger masks). All the world’s a prison ––Lulu’s prison. The restraints of Victorian propriety squeeze everyone to their inexorable fate.

Chase’s condensation of the Wedekind plays has been especially masterful. Confronted with a massively discordant text––a visionary pioneer of the modern sensibility, lacking any precedents, Wedekind at the turn of the century seemed to lurch forward, bludgeoning his way through the theater and producing works which careen in tone from ludicrous melodrama to symbolist expressionism, from Grand Guignol self-indulgence to proto-Freudian analysis––Chase has contrived a structure capable of suggesting the chaos of the Wedekind text while at the same time honing its themes to a precise conclusion.

The film is built like a funnel, moving from the wildly disparate and highly stylized material of the opening through a tightening spiral to the grizzly naturalism of the film’s extraordinary last scene. Rather than fight the text’s seeming out-datedness, Chase has rolled with it, presenting the first three-quarters of the film as a silent movie with title cards, thereby allowing the situations a certain ironic distance which, paradoxically, affords just enough perspective to establish their lasting contemporaneity.

This wizardly artifice furthermore allows Chase the opportunity to marshal as soundtrack some of the parallel passages from the Berg opera––to uncanny effect. What we see are characters embarking on their hysterical rampages, seizures of promiscuity and jealousy––what we hear is the magnificent Berg score. The German of the lyric plays like some utterly unmediated metalanguage of passion, the clash of inner voices somehow as immediate as it is foreign. But Chase’s whimsical convention of the silent movie, title cards and the Berg score really pays off at the very moment he dispenses with it. The film moves from farce to tragedy, from stylized to naturalistic presentation, from music……to silence. For the final fifteen minute sequence, Lulu’s inevitable rendezvous with Jack the Ripper––shot almost entirely in one long dark take––the seduction is intensely erotic, gentle, a modulation of touch and whisper––the murder is razor sudden, the screams welling up as the first and last authentically inhabited sounds of the film. The effect is utterly wrenching.

It is this last scene which has proved so controversial. Throughout the earlier part of the film, Chase is moving through familiar late-Victorian territory. His Jack the Ripper, however, is an entirely original and deeply troubling creation. In films like Pabst’s Pandora’s Box (or the more recent version of this fable, Looking For Mister Goodbar) the murderer is portrayed as either deeply neurotic or desperately compulsive: he seems to murder against his will. In Chase’s Lulu, however, a film in which all the prior male protagonists are portrayed as ineffectual wimps, Jack (played with phenomenal self-possession by Thomas Roberdeau) strides onto the screen as the first virile, sympathetic male character. (He is played straight, no costumes, as if he’d just walked out of the audience and onto the screen.) In his intensely moving seduction scene, he is the first to involve Lulu on a kind of primal I-Thou level, seeming to address her complete being. To suddenly find this lovely, integrated man hacking his love to death is scalding.

Of course, for Chase, the wrenching effect is the whole point. He is not interested in realistic character portrayal; what he’s after is almost mytho-poetic in scope. And for him, Lulu’s is the allegory of woman miscast, continually rendered the passive vessel of other men’s proprietary fantasies (fantasies which in turn possess and destroy them as well), who is at last offered liberation through her first active choice, a choice which, paradoxically, is only an active receptivity in her own demise. For other men she was merely a prop (a property to be paraded, a buttress to their masculinity) ––but in her relationship to Jack she can at last actualize herself….in death. But of course, on another level, Chase’s interpretation is utterly ludicrous, because she’s just as much a prop to Jack; she’s the occasion for some bizarre metaphysical blood ritual of his own––no more, no less. And many in the Filmex audience, at any rate, weren’t about to celebrate this “liberation”.

At one level the question of whether the film’s perspective is misogynist or on the contrary feminist echoes similar questions that have been raised for years concerning Freud, Strindberg, Wedekind, and other central European modernists; and as with those controversies, it turns on whether the works are intended to be read as descriptive or prescriptive. But in Chase’s production the question is further complicated by the director’s un-abasedly gay bias and sensibilities. (Most of the ineffectual males in the first part of the film read like one-dimensional parodies by gays of uptight straight men.) But this too cuts both ways. Chase seems to be saying that liberation, female or gay or black or turquoise, consists not in laws or movements but rather in a personal self-transformation whereby one no longer allows oneself to be used as a prop in the Other’s psycho-system but rather moves toward realizing one’s own innermost potential (even if, as in Lulu’s case, the only authentic choice is death). But in this film, what else is Elisa Leonelli, the bewitching nonprofessional who incarnates the role of Lulu, but her director’s prop? (“I just embodied his fantasies,” Leonelli told a Filmex press conference. “I was the vessel for him to pour through his ideas.”) And what are we to make of how he wields her? Some women in the audience felt defiled by the experience: they felt the film had been made by a man who simply hated women. Others, on the contrary, were profoundly affected by the film’s unusually sensitive approach to sensual themes, one which they often found lacking in the work of more macho-oriented directors.

Few, at any rate, were left unmoved. And the film was rich enough to contain a wide diversity of readings. The controversy arose not out of any haphazard flaws in the film’s conception but, on the contrary, because with meticulous precision, Chase had come very close to the nerve on some highly vexing issues.

LULU TRAILER (2 Minutes)

NOTES FROM THE DIRECTOR (2021)

A half-century has passed since Lulu made her appearance in my life. As a college student I discovered “new” music—mostly atonal—and Berg’s opera was high on the list of my favorites. I spent many an evening mulling through the great moments in Lulu. Lulu led me to Frank Wedekind. His perverse ideas of theater, his mixture of comedy, satire, slapstick with high melodrama and tragedy made his strange work matter to me. It was for me both challenging and highly original. Because of this, it also made his work very difficult to stage. I tried. I directed and designed a production of Spring Awakening for my senior project at Bard College in the mid 50’s.