Your Custom Text Here

Four decades of opera productions using film and projection—from Washington Opera; Opera Theater of St. Louis; Kennedy Center; Chicago Lyric Opera; Los Angeles Opera; New York City Opera; Glynebourne Opera, England.

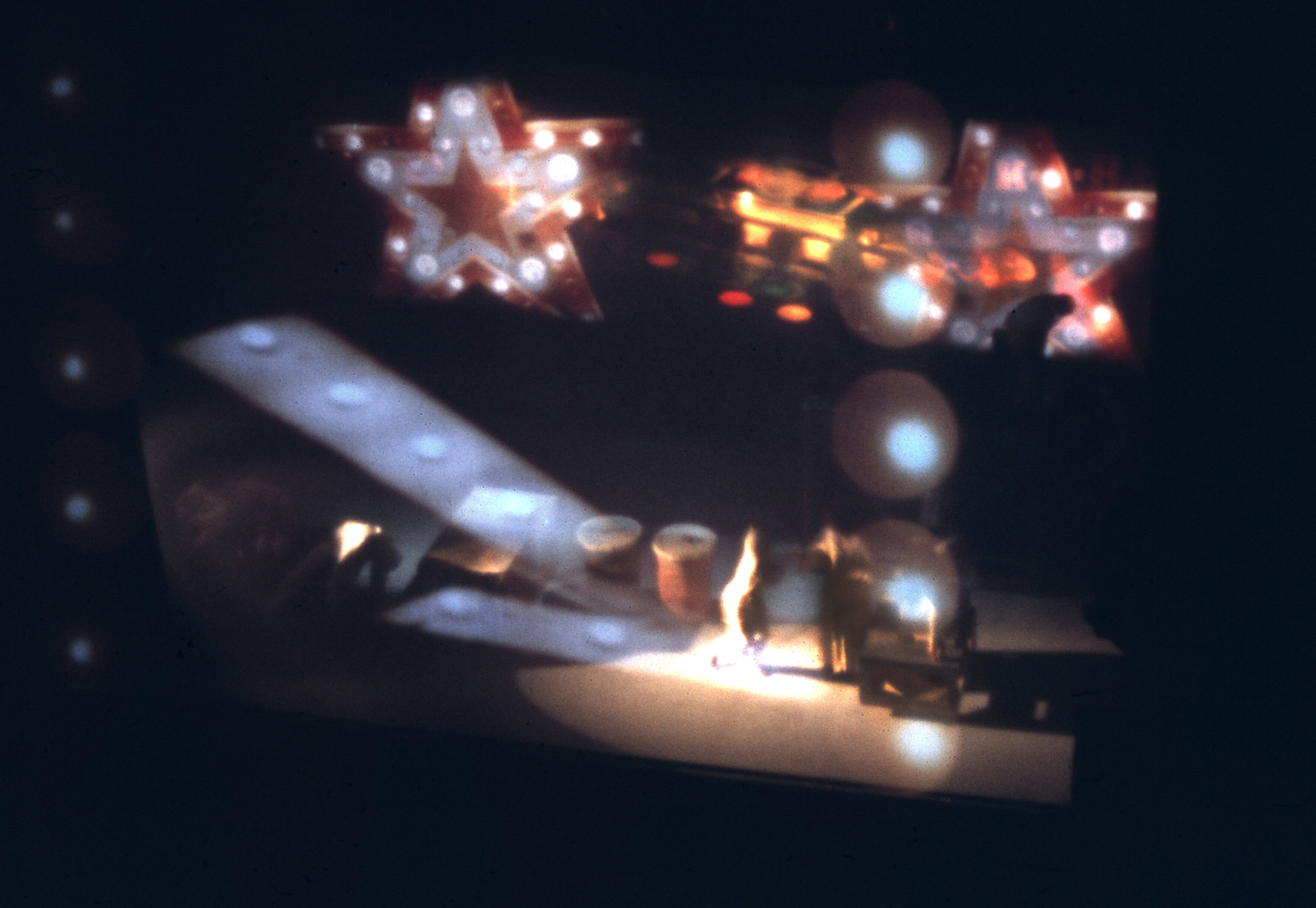

Two productions in opera, both appearing in different cities in 1968-69, introduced the use of film & projection in American opera. One of the first uses of a filmed sequence in American theater appeared in 1968 for the Robert Joffrey Ballet. In the ballet Astarte. a film sequence was projected at the back of the stage while dancers interacted against the images. The filmmakers Emil Ardilino and Gordon Compton then were asked by the renegade opera director, Frank Corsaro, to try something similar for his production of Janecek’s The Markropolous Case at the New York City Opera. At the very same time Richard Perlman, the director of the Washington Opera Society had approached San Francisco artist/sculptor/filmmaker Ronald Chase to design a production of Britten’s Turn of the Screw. Chase was struggling to complete his first short film, Fragments, and anxious to have funds to finish it, agreed to design the opera only if he could use film. He was given permission to do what he wished.

Turn of the Screw opened in a drafty Lisner auditorium in the fall of 1969. Chase had come up with a format that used multiple projections from front projectors to create a single image, and others simultaneously on a rear projection screen from the back of the stage. Thus the players played behind a transparent scrim (on which images and film were projected) sandwiched between screens with images behind them. The opera’s scenes were divided by musical interludes, which allowed films to set the mood of each new scene. The production surprised critics though many dismissed film as a gimmick that was distracting. However, three people became inspired by what Chase had produced –– the head of the Washington Opera, Hobart Spaulding and directors Frank Corsaro and Richard Perlman.

Washington Opera Society became the company that carried the banner of Chase’s ideas for film and projection forward for the next four years, Following an overwhelming critical success with Delius’ Koanga in 1970. Ginastera's Beatrix Cenci opened the Kennedy Center in 1971, The Seattle Opera premiered the Who’s Tommy the same year, and Delius’ Village Romeo and Juliet followed in 1972.

Innovations with projectors, lighting design, minimal set pieces replacing scenic design, scrims over the orchestra pits to block out reflecting light –– these were the elements that had to be invented, rethought, and (in case of the orchestra scrim) fought about with unions and musicians.

This production reinforces the impression that Chase had worked out one of the most exciting developments in the history of operatic stage presentation There can be little argument about the expertise with which the material is handled. This really is a new dimension in opera.

Harold Schoenberg, New York Times review of Die Tote Stadt 1975

With the critical successes of the Cosaro/Chase productions - New York Opera’s Die Tote Stadt In 1975, St. Louis Opera Theater’s Fennimore and Gerde and the Lyric Opera of Chicago’s Die Frau ohne Schatten, more and more opera houses began their own productions using projection and film. Today these techniques are used yearly in productions throughout the world. But without the early work and dedication of Frank Corsaro and Ronald Chase, these techniques would have taken many more years to emerge.

These opera pages help you follow projection and film growth and development in detail.

590 Tahoe Keys Blvd, South Lake Tahoe, CA 96150